Since starting my PhD research in October 2017, I’ve had imposter syndrome. Not only in regards to my research, in which I have spent hundreds of hours in a room alone trailing through literature that I’m not academically trained to fully comprehend as a ‘designer’, but also in regards to my tattooing practice, where irrespective of the number of tattoos I produce, I feel like my skill level remains the same. I was under the impression that this is normal in the first few months, but in time it would gradually become less prominent. It hasn’t.

Despite reassurance from all three members of my supervisory team that my research is going well, and despite reassurance from my mentors/colleagues at the tattoo studio that my tattooing practice is legitimate, the insecurity I have felt regarding my work has remained. When the global pandemic of covid-19 happened and the majority of the UK had to self-isolate from the middle of March 2020, I was no longer able to work in the storage cupboard/office that I had been situated in within the university, or tattoo in the studio, with the change of environment allowing for a subtle change in perspective.

Since self-isolation, I have been attempting to write-up parts of my thesis that are possible to write without on-going studio practice. This includes the formal writing of the autoethnographic material I’ve produced, and a contextual overview of existing understanding of contemporary western tattooing practice. One of the on-going themes of concern within my research is adhering to the very restrictive 40,000-word count that practice orientated PhD research allows, while trying to write about a discipline that is as social as it is practical. After having writing up 50% of one of my six chapters on the non-material role of the tattooist, in which I draw upon my autoethnographic writings, I found that I had hit over 30% of my allocated word count. In an effort to reduce the word count, I have since rewrote the chapter as a potential academic journal entry, which is currently under reviewal for publication. If published, this would then allow me to summarise the findings, and expand upon them within my thesis.

Attempting to write a literature review without access to a library is also difficult. Though with many disciplines, academic journals are the primary source of up-to-date citation, tattooing hasn’t been subject to the same manner of scholarly analysis for the most part. Matt Lodder (2018) has described much of the academic work on tattooing as ‘research tourism’, in which academics use tattooing as, “…a diversion or offshoot from their primary research angle” (in TTTism and Schonberger, p.503). This is true of much of the academic work on tattooing, which is primarily concerned with the tattooee, rather than the tattooist, and asks questions regarding tattoo motivation, marketplace, social behaviour, etc. This has resulted in relying on a few key texts (namely Sanders and Vail, 2008) and more contemporary coffee table style books, for the material of relevance. This has meant purchasing them to own, as many only exist in print and the library is not accessible for the foreseeable future.

Though the gap in the literature was apparent prior to writing, it was not until formally attempting to write it up that I recognised the potential value of my own research. Perhaps my attendance at various other training workshops and conferences from numerous other fields had amplified my own insecurities surrounding my applicability as a researcher (very frequently I have left an event such as those described and felt like a working-class fraud with insufficient intelligence to make a meaningful contribution or ability to write a decent piece of academic material). While critically analysing the literature against my own research questions, I began to recognise the void my work would be able to partially fill. In having to work from home, I have been in the company of the non-professional version of myself, with a new routine and lifestyle that is not transferrable to the pre-quarantine world. Despite all the problems that this brings with it (there are legion) it has also allowed a little more space to recognise the value of my work and my validity to construct it.

What do we mean when we talk about tattoo 'meaning'?

While re-visiting numerous articles surrounding meaning and identity within tattoos (such as Sundberg and Kjellman, 2018; Kjeldgaard and Bengtsson, 2005; Carmen, Guitar and Dillon, 2012), I noted the tendency for simplification of findings and the implication of meaning as fixed, or as Sullivan (2001) terms it, ‘dermal diagnosis’ (p.17); as if a tattoo received at the age of 18 means the same thing as it does at the age of 30. The straight-forward presentation of meaning of tattoos in academic literature (i.e. a lighthouse design symbolising guidance) fails to recognise layers of nuance that exist as a motivation for tattoo acquisition. When conducting research involving interviews with those attaining tattoos on their specific motivation, the assumption is that there is some clear-cut meaning that is in the realms of communicable vocalised explanation. It is also assumed that the design denotes singular authorship; as if the way the tattoo appears on the body is the result of an individual interaction, rather than a contingently collaborative process between tattooist and client, as is often the case.

I considered the nuance of tattooing meaning by drawing upon my own experiences of being tattooed with a subject matter that is sentimental in nature; my deceased dads handwriting. My dad suffered from severe depression and subsequently, alcoholism, from an early age in his life. In the 1970’s, he founded a progressive rock band named, ‘Cirkus’ (in reference to a ‘King Crimson’ track, from the album ‘Lizard’) in which he was the main song writer and drummer/backing vocalist. The band enjoyed relative success, releasing their first studio album in 1973. Growing up, my dad would often play the music he had created on Saturdays when I would go and visit him, since his separation from my mam at a very early age. I remember not being particularly interested in the music, which was an extension of the turbulent relationship with him that I had more generally due to his absence and the feeling of discomfort I had in being around a guardian figure who was inebriated, without understanding what inebriation really was.

As I grew older and began to become interested in music and learning to play the guitar, I turned to my dad for lessons. He was able to teach me some basic chords and was enthusiastic about my interest, however his ongoing relationship with alcohol had led to a diminishment of skills and ability to teach. This then led to further frustration, continued depression, and a stronger reliance on drinking. My relationship with my dad fluctuated through adolescence, but my visits to see him eventually became more out of desire than duty. We introduced each other to numerous musicians, and I would often show him new pieces of music I had written with the sincere desire to impress him, and I trusted in his musical knowledge and feedback. He was always very supportive.

As I began to become to tattooed on my right arm over 12 years ago, I formed a good relationship with the tattooist. He was around 15 years my senior, and in addition to representing the romance of tattooing that I found so alluring, I admired his ability to lead a lifestyle that allowed him to engage with a creative medium and pursue his own interests. Though not old enough to be a paternal figure to me at that age, he played a significant impact in my personal growth through the example of adulthood that he represented, and that I aspired to achieve for myself. He created a full sleeve over the course of a year and a half, with one of the latter pieces being a scroll of paper in a bottle on my inner forearm. The sleeve is in a traditional-western inspired style, with no specific meaning attributed to the subject matter for the most part, which was chosen based on visual appreciation and resonance with the practitioner. Though my dad didn’t like tattoos, he always advocated personal sovereignty, and so never discouraged my choice to become tattooed.

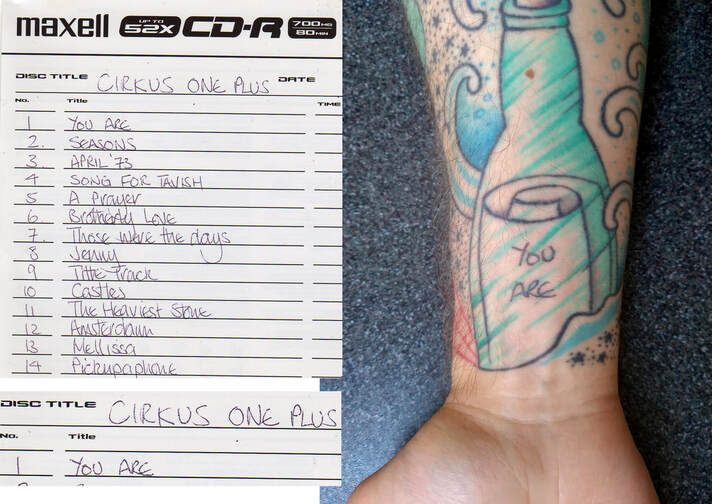

As the years passed, my relationship with my dad matured, and he went through phases of becoming more and less ill. I became more appreciative of his music, and felt like I finally understood it after practising music myself for a number of years. I actively listened to the CD of his first album ‘one’ and resonated specifically with the first track, titled ‘You Are’. The original LP pressing of his album is a collector’s items amongst prog-rock connoisseurs and is very rare thus valuable. My dad sold both his records and the CD versions of his music for money to survive, but had made sure he made a CD-R copy before doing so, with hand written track listings. I interpreted this act to be representative of the extremity of his situation; he created an authentic and creative expression of beauty that symbolised a significant achievement, that was only ever going to monetarily increase in value, but he was in a position where he needed to trade this for money for his survival and sustenance of his addictions.

As he grew older, his resistance to his own ageing furthered the tendency to drink and the walls of his rented apartment in which he lived alone became more tainted with stagnancy and sadness. He died of heart failure after what is believed to have been a deliberate decision to no longer take his medication on Easter Sunday 2016, and his body was found on the floor of his passageway 4 days later by my sister. She had a key and visited after not hearing from him when trying to make contact and becoming concerned. His funeral commenced around a week later, and I carried the side of his coffin containing his body into the church alongside his brother and my cousins, while the track ‘You Are’ played. I hadn’t fully accepted the grieving process until this point. As the ascension of tones of the introduction to the song played in rhythm with the pace of my footsteps, accompanied by the weight of my dad’s body on my shoulders and the years of burdened suffering that it had housed, I felt a wave of emotion pass through my body in perfect synchronisation, to be expelled in an outpouring of cathartic tears as I took my seat. The song played out as I waited for the service to commence and my grief to begin its course, as part of a curriculum that I am still undertaking.

Shortly after my dad’s death, I made the decision to hand in my notice for my job as a content editor in the fashion industry (a position I had no interest in, and had taken solely as a means of generating income to survive), and travel to Asia where I had previously felt at home, until I ran out of the small pot of money I had saved. My hope was that I would find employment in Thailand, Indonesia, or India, and be able to live there for some time, and the decision to go was inspired by the reminder of the impermanence of all things that my dad’s death at the age of 62 presented. When I ran out of money from travelling after 3 months, I returned to Sunderland, and in an effort to not live an existence based on fear in favour of one based on fulfilment, I reached out to the owner of the Studio in which I now work as a tattooist.

I was originally introduced to the studio owner on the recommendation of the tattooist who had completed my sleeve, after I requested a realistic style tattoo. He told me that there was another tattooist who had recently opened a private studio and was breaking new ground with the work he was producing. Although my existing tattooist could have taken the money and executed the tattoo, he recommended an alternative tattooist based on what served my interests, over his own (an unconventional notion in preceeding decades of tattooing). After meeting the studio owner, I went on to get both my foot and full sleeve tattooed by him, and formed another centrally important figure in my personal development. When asking for a tattoo apprenticeship, he had told me to go to university and do a course relating to visual arts, and then he could consider the position based on what I had learned. After progressing from a foundation degree to a master’s degree in illustration over the course of 5 years, I felt that I wanted to pursue a career and generate enough income to live independent of my mam, and so sought a full-time job rather than pursuing tattooing.

When I got back home, on a whim, I contacted the studio owner, who was now in charge of a studio of over 10 tattooists and internationally award-winning tattooist, as well as inventor/product developer. When I asked if he was considering an apprentice, he told me that the same thought had crossed his mind, and he offered me a position. In this studio, the tattooist who completed my first sleeve was now a full time resident, and I was able to learn from him amongst numerous highly-skilled others. Six months later, I created my first tattoo on the studio owners arm who had given me the apprentice role, which to this day is the most technically poor and simultaneously meaningful tattoo I’ve created to date.

After working in the studio for around 8 months and dealing with the grievance process of my dad in the various stages, I made the decision to have his handwriting tattooed on me. The handwriting was found on the sleeve of the CD-R of his first album, written in biro, and was visually distinctive to me from having seen it in every birthday card written to me up until the age of 26 when he died. The first track on the album, “You Are” seemed the most appropriate piece of text to have tattooed for reasons beyond it being my favourite track alone; the track was symbolic of the establishment of a connection with my dad beyond the father-son relationship exclusively, as it was the turning point from which I began to admire and see value in his skillset. It was also the track that acted as a vehicle through which I navigated into the first stages of my grievance process during his funeral. The open-ended nature of the words feels like an answer from him to questions that I haven’t yet asked, that can be interpreted in multiple ways with the consideration of what he might say.

I opted for the same tattooist who completed the scroll of paper in a bottle tattoo for me over 10 years prior to do the piece. The scroll of paper in the bottle was indicative of a message, but the content of the message had thus far not been known. I had the words put into the scroll with watered-down black ink, to emulate handwriting and appeared consistent with the tones of the rest of the earlier executed tattoo. It was important to me to have the piece completed by the same tattooist who created the original piece, due to his impact on my path and my associated memories of a time in which I was becoming tattooed and being birthed into adulthood into a world that still had my dad in it. The tattoo being completed by that particular tattooist after a significant period had time had passed and changes in our lives had occurred, in a context where I was now working alongside figures who had already unknowingly shaped my personal growth, contributed a layer of nuance to the ‘meaning’ of the piece.

Carmen, R. A., Guitar, A. E. and Dillon, H. M. (2012) ‘Ultimate answers to proximate questions: The evolutionary motivations behind tattoos and body piercings in popular culture.’, Review of General Psychology. (Human Nature and Pop Culture), 16(2), pp. 134–143. doi: 10.1037/a0027908.

Kjeldgaard, D. and Bengtsson, A. (2005) ‘Consuming the Fashion Tattoo.’, Advances in Consumer Research, 32(1), pp. 172–177.

Lodder, M. in TTTism and Schonberger, N. (2018) TTT: Tattoo: A Book by Sang Bleu. 1 edition. London: Laurence King Publishing.

Sanders, C. and Vail, D. A. (2008) Customizing the body: the art and culture of tattooing. Rev. and expanded ed. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Sullivan, N. (2001) Tattooed Bodies: Subjectivity, Textuality, Ethics and Pleasure. Westport, Conn: Praeger.

Sundberg, K. and Kjellman, U. (2018) ‘The tattoo as a document’, Journal of Documentation, 74(1), p. 18.

Adam McDade

Tattooist at Triplesix Studios

AHRC NPIF Funded PhD Research Student at The University of Sunderland

RSS Feed

RSS Feed