(Names changed for confidentiality purposes)

Linda came into the tattoo studio on a Friday afternoon to make an appointment for a small piece. As a junior tattooist, part of my role still involves helping out on the desk (booking client appointments, taking payment from clients etc.), which I was doing on this occasion. After greeting Linda who told me that she wanted a tattoo on her ankle area, I asked to see a photograph of what she was hoping for. At an estimate, Linda was aged somewhere around her 50’s. She was of average weight and tanned complexion, with around 2 or 3 relatively large (distinguishable from a distance) tattoos on her arms, and as I came to see when she showed me where around her ankle she wanted the tattoo to be placed – a smaller text tattoo of a name on her ankle.

It is often the case (in the post-industrial town of Sunderland, at least) that when discussing tattoo designs/placement with clients who have fairly limited tattoos and are of a particular age, that expectations may not be realistic. An example may be that the client wants a large piece of text tattooed in a small area – unaware that the tattoo ageing process may make the piece illegible over time. Similarly, a client may request a portrait of their dog / child / partner, but be only able to provide a photograph that is of low resolution for the tattooist to use as a reference which would be insufficient to complete the piece with desirable quality. This wasn’t the case for Linda however, and it appeared that she had considered the piece by her confidence in placement, size, and design simplicity. This consideration was also apparent in her tone and demeanour, which appeared to be confident and defined.

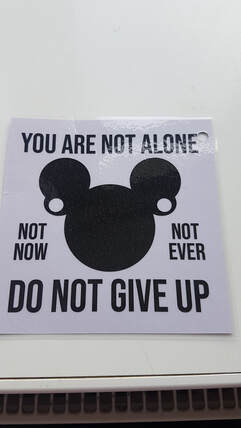

Linda showed an image on her mobile phone, which she had indicated she would like to be tattooed above her ankle. The design looked as though it was from a sign that had been placed in a public space such as a train platform community notice board, or in a doctor waiting room, and read, ‘You are not alone. Not now. Not Ever. Don’t Give Up’. In the centre of the design was a silhouetted icon of the Disney character Mickey mouse, but with an additional circular silhouette with a hollow inside that was placed on each ear, to suggest the ears where expanded. On initially looking at the design, I had not considered that the circular shapes inside of the ears where indications of expanded ears, as I was looking at the image from a purely pragmatic standpoint in regards to its suitability as a tattoo, to be placed above the name already tattooed on the ankle. Though I recognised the design was not the traditional portrayal of ‘Mickey Mouse’, the significance of the deviance from the original icon at that point was not relevant to my assessment of the design translation from screen/print, to skin.

Linda stated she wanted the silhouette to be coloured ‘a nice purple’, which she reinstated when making the booking, and around 2.5 x 2.5 inches in size. I assured Linda that we could gather together some pre-mixed coloured ink bottles on the day, and she could select the purple pigment of her choosing. I told her that the tattoo should take around an hour, and I was able to do it for her for £40 (the studio minimum charge, and my hourly rate). Linda was suitably satisfied with this, and booked to have her tattoo on the following Tuesday, leaving the full tattoo cost as a non-refundable deposit. When leaving a deposit, it is necessary that the member of desk staff inform the client that the deposit is non-refundable prior to taking the money. I made Linda aware of this, and she confidently assured me that she would definitely arrive for her appointment, which I didn’t doubt. I asked Linda to email me the image, from which I would prepare a design. This is ordinary practice within the studio and ensures that the reference image from which the tattooist produces a design adheres to the clients request appropriately.

Design process

Around 45 minutes from leaving the studio, Linda had emailed the image to me, from which the design was to be produced. The image was a photograph of a laminated sign taken on a slight angle. I downloaded the attachment and copied it into an Adobe photoshop a4 document, where I had intended to see if I was able to make a stencil from the photograph. Due to the angle, I was not, and so I utilised google image search to find an image for the search, ‘mickey mouse head icon’.

The images where all silhouetted icons, however it was only the outline of the shape that I required, and so I intended to generate a line drawing from the existing shape to utilise as a stencil and inform my tattooing process. A silhouette was isolated, copied, and pasted into the already open photoshop document. As the icon was placed alongside the image that Linda had sent to me, I remembered that the intended design included the circular shapes in the ears. I was still unaware that these shapes where indicators of expanded, but wanted to honour the original design, and so using the shape tool, created a white circle that was then placed over the ear area of the design. The placement was informed by the original photograph, and once the left-hand side of the image appeared correct, the full design was marked in the centre, the left-hand side copied, and then mirrored / placed over the top of the right-hand side of the image to ensure perfect symmetry.

This composite design was then selected using the magic wand tool, before being contracted by around 4 pixels and feathered slightly, for the selection to then be deleted, leaving an outline of the shape that could then act as the stencil. I composed the shape on a sheet of paper 4 times at varying sizes, and followed the same outlining procedure for a version of the icon without the additional edits to the ears. These versions of the design where also created in 4 sizes that reflect the first set, and placed on the same piece of paper. The sheet was then printed, to be shown to Linda on the morning of her tattoo so that she could pick a suitable size for her tattoo (though deviance in size from those which are printed is possible, and the sheet is merely an informed guideline in accordance to clients original stated size for the tattoo). Both versions of the image where included (traditional Mickey mouse and expanded ear mickey mouse), as at this point I was unsure if Linda simply was unable to locate a version of the design without expanded ears for any reason.

The design sheet was placed in my tattooing booth on Saturday afternoon, in preparation for the appointment on Tuesday morning when the studio opened. Linda arrived at around 10:45, 15 minutes ahead of the appointment time, and had brought another person with her. I greeted Linda with and intentional but sincere familiarity of tone, expressed through an informal “hello’, and gave her a consent form to complete (mandatory for every tattoo session, irrespective of the client is new or returning). I had assumed that Linda’s companion was simply company for the appointment, which is very common, however she had asked if she could also be tattooed with the same design, on her forearm. I checked the schedule, calculated that I should have both tattoos completed by around 1pm which would allow me to cover the front-desk so that my colleague would be able to have her 1pm lunch break, and said that I should be able to complete the tattoo for Linda’s friend directly after tattooing Linda.

Lindas companion was named Samantha, and appeared around 10 years younger than Linda, and had a similar demeanour of sincerity but slightly less confident and more timid. I later found out that Samantha was Lindas cousin, who had decided to get the tattoo after hearing that Linda had booked in for the piece. After both clients had filled in their consent forms, I brought over the design sheet and explained that I had included both version of the design (Mickey mouse with and without expanded ears), and asked which they would prefer. Confidently, they both opted for the expanded ear version of the design without any hesitation, confirming that the design was of significance. It was at this point that I recognised that the circles in the ears where expanders, and that the tattoo was likely a memorial of a person who both Linda and Samantha had lost. I asked both clients to take a seat while I cut out various sizes of the design, which I then brought over to them to place next to the area to be tattooed so they could gain a more accurate understanding of the placement.

After the desired sizes where selected, I created a stencil to work from, dealing with Lindas first as she would be getting the tattoo before Samantha. During this process, I thought back to the image that was originally sent to me as reference and the words. I couldn’t recall the specific words, but I remembered them as being something to the effect of “you’re not alone” and “never give up”. It was at this point that I made the inference that the loss both Linda and Samantha suffered was due to suicide. Though the tattoo as a symbolic memory of a specific individual was stated, the cause of death never actually confirmed and it did not feel appropriate to ask for details. It later transcended that person being memorialised was young, had expanded ears, and named Michael. My recognition of the seemingly obvious symbolic significance of the piece was so delayed due to my focus on the material nature of the brief on first encounter. I was not looking at the image to draw out any particular meaning, but merely considering if the design would work as a tattoo. I recognised that when performing the role of a tattooist, my interpretation of the same situation would be different than when not performing any specific role, as my assessment of the situation would not be guided by any particular requirements to be fulfilled.

Tattooing Process - Linda

As I now became aware that the tattoo I was completing was not merely pictorial, but perhaps ceremonial, the felt sense of responsibility was amplified. Interestingly, it was not the pressure to ensure the tattoo was well-executed that I felt the most crucial aspect of my role at this particular point, but my desire was to ensure that both clients where suitably comfortable at all points in whatever way possible seemed of a higher priority. I asked Linda and Samantha to come over to the booth and brought a chair for Samantha to sit in while I tattooed Linda, and vice-versa. As we walked over and I prepared Linda’s skin surface to be tattooed, I made a particular effort to keep my conversation tone light, while simultaneously trying to welcome any depth of content that she would like to share. My tone of voice contained a ‘brightness’ to try and communicate openness and acceptance of whatever Linda wanted to share with me, and when Linda started to speak about Michael, I asked questions that elaborated on the content she was already discussing (such as his taste in music and how his brother is emulating it now). The questions where along the lines of ‘…so did Michael play an instrument?”, and I had tried to ensure that what I was asking was not overly personal, but personal enough for Linda to understand that I was willing to listen to whatever she was comfortable to share, and create a space for her to do so.

The duty I felt to be present in such a way is not unique to being tattooist and a simple human instinct, however as memorial tattooing is commonplace, tattooists may more commonly have to develop skills in being present to ensure client comfort. While waiting for the stencil to dry, I poured ink into my ink caps, attached the appropriate needle gauge to the tattoo machine in accordance to the stencil thickness, and went to the bathroom to tie back my hair as a health and safety precaution. Linda and Samantha talked between each other at this point, and I offered them both a drink of water between the other tasks. I brought Linda 3 different tones of dark purple to choose from for the colour of her tattoo, and kept the bottle that she had selected on top of the booth area to refill for when it came to tattooing Samantha, ensuring that the tones matched.

After around 10 minutes when the stencil dried, I adjusted the tattoo bed so that Linda was able to sit up asked her to stretch the tattooing leg out straight, and began the tattooing procedure, starting with the outline. As the procedure continued Linda told me that after booking her appointment with me she had looked at my social media accounts by following the links that are included on my appointment card. She recognised my surname – McDade, and contacted my uncle of the same surname who she is friends with, to see if we were any relation. My uncle informed her of our relation, and that I was his brothers’ son.

It transpired that Linda was active in the music scene during the 1970’s, and regularly went to local gigs. My late father, ‘Blue’ (as he was ironically referred to as due to his high decibel and distinctly decipherable booming laugh that it is likely was only ever present as a mechanism to deal with his social anxiety and life-long depression, and so actually ‘meta-ironic’), played in popular progressive rock band named ‘Cirkus’. Linda told me how she had known my dad and had enjoyed watching his band perform many times. She expressed her condolences for his death in April 2016, in which he had suffered heart failure as a result of what is believed to have been a deliberate failure to take medication resulting in the ending of a life that was burdened by a serious of health conditions such as prostate cancer, deep vein thrombosis, fibromyalgia, life-long depression and alcoholism. His 62-year-old body was found on the floor of his apartment in which he lived alone by my sister who had a spare key, around 4 days after his death based on the coroner’s estimation. My relationship with my dad was very positive overall, though we were never able to be as close as we both would have wanted due to his excessive absence and unreliability in my childhood and adolescence which was largely the result of his self-medicative relationship with alcohol to deal with his depression. His death was simultaneously sad and relieving, as his health issues made his premature death an inevitably that had been anticipated for over half my adult life, after being told to ‘expect the worst’ when visiting him off and on in hospital over the past decade and a half.

Linda’s expression of condolence made me aware that she was already informed of my own loss, and we had a shared experience of grievance. As I continued to outline the tattoo – an already intimate procedure in which I am touching the clients body with my hands, with the remainder of my body in close proximity and with the client positioned in such a manner that is aimed towards informal relaxation (it is important to ensure a client is comfortable when they are being tattooed and have them in a position that maximises this), the intimacy of the exchange became more nuanced. I stated that my comparative loss was not the same and that Linda’s was no doubt more severe, as Michael was significantly younger than my Dad, who’s death had been anxiously anticipated far ahead of it happening.

As we spoke through the tattooing process, switching from the outline to beginning the colour, the exchange felt significantly more personal than tattooing a standard client. Linda’s design choice was semiotic in its communication of loss in that she had chosen to have it embodied, and she was additionally aware of my personal biographical narrative regarding my relationship with my dad. Though tattooing for a longer period of time invites more informal and holistic conversation than other service industries might (such as massage), the personal involvement in this instance required a combination of professionalism (ensuring client physical comfort, checking that they are OK in regards to the pain etc) and personal presence (that is, being present as Adam, with my own sense of self, rather than simply as a tattooist).

I told Linda that her skin was accepting the purple coloured ink very well (sometimes purple can be difficult to appear saturated depending on client skin type), and she appeared to be completely comfortable with the physical pain. She stated that she did not believe that tattoos hurt her much, and I relied on my canned tattooist response (though true) that women tend to be able to tolerate pain better than men, and that comparatively to child-birth tattoos must a ‘walk in the park’. Canned comments such as this are useful as tools for the client to recognise that they are dealing with the pain very well, and to try and help them to feel positive. It was apparent in Lindas demeanour that the pain was not actually affecting her due to her stillness, which may be inferred to be comparatively easier to handle than the grievance she was experiencing.

On completion of the tattoo, I wiped down all the excess ink and asked Linda if she would like to take a look at it in the mirror. On the way to the mirror, she showed Samantha who had been seated during the process, who expressed her fondness of the tattoo. Linda returned with a smile, stating she was very happy with the piece and thanking me, before her tattoo was wrapped in cling film for protection. It felt more appropriate to hug her than simply thank her for allowing me to do the tattoo for her, with the professional environment in which the tattoo was produced being the dominant deterrent to such an exchange. I asked both Linda and Samantha if they could please take a seat at the front of the studio so that I could clean down the work station and prepare it again for Samantha’s tattoo. As I proceeded to remove cling-film and protective layers from the surfaces and into the toxic waste bag, I considered how this creation of space shares parallel to that of a shamanic healing facilitator, in which a ceremonial environment is created and cleansed (though through smudged sage, rather than medical grade disinfectant) for trauma to be dealt with and navigated with the assistance of a practitioner. It was not the role of ‘shaman’ in its full array of responsibilities that I thought was comparable, but rather the attribute of the role as a facilitator for an experience.

After taking the time to set up the space, I asked Linda and Samantha if they wanted to return to the booth. Linda sat in the chair with her mobile phone in her hand, and I noticed she was sharing a photograph of her new tattoo to her Facebook account. Samantha had a far less confident demeanour than Linda – she was much shyer in her mannerisms but wore a consistent smile. The smile seemed authentic and sincere, but as though it was just a veneer to cover up some unbearable pain that it would not be socially acceptable to make visible to a stranger. It was a genuine smile, but it was present to express politeness, rather than happiness. Though given the motivation for the tattoo, a sense of sadness was to be expected, It felt as though it was sourced in something more deeply rooted than one particular event or reason.

Samantha had chosen the forearm as the placement for the tattoo rather than her ankle, where Linda had placed it, and requested for it to be slightly smaller in size. I vocalised that small, often almost invisible hairs can interfere with the tattoo stencil to Samantha. As I shaved the discreet white-coloured hairs from her arm in preparation for the stencil, she told expressed that she feels she is hairier than she ‘should’ be in an almost apologetic tone. I assured her that it is very normal and natural to have body hair, and that she didn’t have to worry. The tone of shame that I detected confirmed that the other aspects of her nonverbal communication that lead to my inferences of her vulnerability where perhaps correct, and I was able to infer their presence through sharing similar traits and characteristic throughout my life. I positioned the stencil on the arm, checked that she was happy with the placement, and adjusted the bed so that she could lay down with her arm out straight on an arm rest.

Though tattooists have different preferences for client positioning when tattooing, I find that having clients lay down assists in the feeling of relaxation, thus helping to alleviate any nerves that may be present. Following the same procedure as when tattooing Linda, the outline was completed with the same needle gauge. As the tattooing commenced, It did not feel appropriate to discuss the death of Michael due to Samantha’s vulnerability. Instead, I opted for more ‘small-talk’ forms of conversation, and learned that Samantha worked in a retail outlet, and would be going into work later that afternoon. She stated that she thought the job was OK, and didn’t mind going in to work. Samantha’s smile was consistent throughout the conversation and the remainder of the tattooing procedure, though her responses (though very polite) where limited, and didn’t prompt many further questions to naturally occur.

It seemed that even speaking was painful for Samantha, which I wanted to respect for her tattoo experience. As I used my non-tattooing left hand to stretch the skin around the area to be tattooed, I felt very aware of amount of pressure that was necessary that I otherwise would not have considered. Samantha’s arms where thin and appeared delicate, and I felt uncomfortable in both putting pressure on her arm and in inflicting the pain that the tattoo process incurs. It didn’t feel appropriate to be causing additional pain to somebody I deemed to be suffering so much already. I contemplated how this feeling has occurred in other scenarios, such as tattooing people who are aged only around 18 or 19, or people who clearly find the pain more difficult to tolerate. I had to consider how my interpretation of my analysis of her situation and character would likely be at least in part my own projection, though perhaps combined with some sense of intuitive understanding.

As I began the colour stages there were no words that were exchanged, but the silence did not feel at all uncomfortable. As the blood rose to the surface of the saturated coloured areas of the tattoo, the process of wiping it away with a baby-wipe and continuing to extract more though the continued tattooing reminded me of my earlier comparison of shamanic healing ceremony and tattooing procedure. The pain that was being initiated coupled with the care that was taken to assure the comfort, and the necessity of the client to surrender to the sensation, reminded me of my personal experiences of dealing with trauma during an ayahuasca ceremony. The blood was the body purging, wiping it away was a means of cleansing, and the finished tattoo was the rebirth and reclamation of the sense of self.

As the procedure finished and after following the usual protocols I wrapped up Samantha’s arm, I attempted to keep the conversation light. Part of Samantha’s vulnerability may have indeed been the nerves she could have been experiencing in undergoing the tattooing process, as there was a sense of brightness in her tone of voice. This may have been the relief of the process being finished, the acquisition of a new embodied signifier, or the assistance that having underwent the procedure had in the grievance procedure. I thanked both Linda and Samantha, who were both charged the minimum amount for a tattoo (£40), went over the aftercare instructions, and said goodbye. They thanked me in return, generously tipped me £5, and left the studio.

The account given is very specific and unique to me as a tattooist, working in the town that I was born, and with the baggage of my own experiences that inform the lens for interpretation of the world and the people with whom I co-exist. Despite this, the nature of tattooing designs that are for the purposes of memorialising a deceased loved one is commonplace, irrespective of location. The tattooing procedure may induce amplified stress than if the piece was purely pictorial given the knowledge of the significance, and the subject matter may not necessarily be in keeping with the tattooists personal taste (as in this example, the tattooists subjective taste should not be relevant). The experience of client care may be require different skills, communication tone, and sensitivity, when dealing with memorial tattoos, and much like therapists, it is not uncommon to inherit the feelings of the client and care for their wellbeing once the procedure is over. Similarly, when dealing with performing memorial tattoos, it is not uncommon to draw upon personal experience in order to relate to the client, and create a mutual sense of trust and space for intimate exchange. This can result in reconjuring emotions in a way that otherwise may not have risen to the surface in an unpredictable fashion.

21st century Tattooing has been labelled a consumer commodity, which it very often can be, however it is important to recognise that not every tattoo is necessarily about the visual output alone, but the process being undertaken. Unlike traditional mediums such as painting or drawing, the tattooist’s role expands beyond the visual practitioner, as contemporary Western tattooing is a service industry. What tattooing has in common with disciplines such as graphic design or illustration is that the practitioner produces an output for a client based on their unique brief. What distinguishes tattooing however, is that the client is an inherent part of the output. Tattooists must therefore be skilled in factors that expand beyond the use of their materials alone, on a contingent and non-hierarchical basis. This blog post aims to serves as an introduction into what some of the necessary skills may be, and give an informed account of what the procedure of producing a memorial tattoo may look like.

Adam McDade

Tattooist at Triplesix Studios

AHRC NPIF Funded PhD Research Student at The University of Sunderland

RSS Feed

RSS Feed