Since the previous post in April 2018, many advancements in the apprenticeship process have been made. The most recent blog post was an account of activity of tattooing fruit skin that was actually conducted in September/October 2017, however since that time multiple tattoos on actual skin have been carried out (72, at the time of writing in October 2018). In order to keep the blog functioning as an up-to-date account of the apprenticeship to professional tattooist transition, and of the evolution of the research as it unfolds, an alternative approach to writing must be approached.

By keeping the posts created in the same time period in which what is being described and considered, a more organic and thus accurate sense of the research journey is made visible. The posts that are to follow are intended to function as a format of dissemination of developing themes of inquiry from my PhD research, that are reflections of my ongoing studio practice.

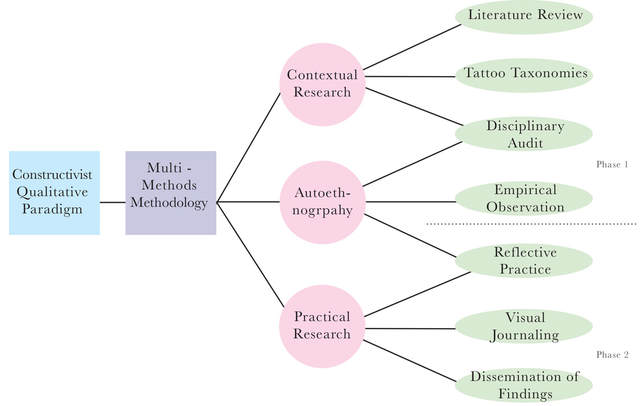

The purpose of the research is to utilise my embeddedness as an apprentice tattooist with a design background to elucidate on and explore the process of cultural production of contemporary Western tattooing. The methodology of my research is shown in the below diagram – included in this post to give an indication of what the future narrative of the blog may look like.

A contextual overview of contemporary Western tattooing is necessary in order to position the research within the field. This includes reviewing the existing literature to discover areas lacking in clarity of understanding that may be pursued. The literature review is continuing to be conducted throughout the research process. Context has also been provided through taxonomizing stylistic approaches to tattooing, categorizing the name of each style in relation to its antecedent style. This is in order to document cultural history and to provide context from a visual and design perspective to contemporary Western tattooing, that the literature review highlights to be absent.

Understanding on the process of cultural production of tattooing is lacking (Lane, 2014). This includes what tools are utilised to create marks of varying visual properties of tattoos, such as ‘liners’ or ‘magnums’, in addition to the process of client consultation, through to design formation, stencil, and actual tattoo. A disciplinary audit of the functioning of tattooing is necessary in order to provide a basis for practical investigation. Methods commonly employed by tattooists for self-promotion (such as the sharing of work on social networking websites, tattoo convention attendance, and guest-artist appearances) would also be recorded in order to document cultural history.

The contextual overview will also be informed by an autoethnographic approach due to my embeddedness within Triplesix Studios as a designer who is working as a tattooist. As stated by Méndez (2013, p.280), “autoethnography allows researchers to draw on their own experiences to understand a particular phenomenon or culture”. Observations or ‘fieldwork’ of the process of cultural production will be documented in order to discover where introducing methods known from design practice may be appropriate in tattooing practice and provide insights that have been demonstrated to be lacking in literature.

Phase 1 of the research provides understanding of context – phase 2 aims to expand on the findings to investigate tattooing as creative medium, using reflective practice and autoethnography. Reflective practice can be understood in accordance to the ideas of Schön; that the practitioner “...may reflect on the tacit norms and appreciations that underlie a judgment, or on the strategies and theories implicit in a pattern of behavior” (1984, p.3).

Tattoos created would be evaluated through the documentation of its concept through to finished article in the form of writings, photographs, and presentation of methods used to create the design (visual journaling). A dated document of each tattoo created is also being maintained for reflective purposes. This process of visual journaling addresses the gap in knowledge, while also providing a basis for tattooing as both practice, and praxis (utilising knowledge gained from phase 1).

After gaining authentic understanding of industry processes and confidence in tattooing, alternative models of practice would then be investigated in keeping with methods known as a designer. This would correspond with the processes identified for creativity by Mace and Ward (2002, p.184) who state that in order to enrich, expand, and develop a project an artist “engages in a process of idea development and extension through exploring the intricacies of that concept, building up a richness of form and content” (2002, p. 184). Implementing methods from design practice in tattooing is a means of investigating how contemporary Western tattooing may be enriched.

In order to disseminate findings, multiple conference attendances will be made as the research unfolds, presenting emergent themes appropriate to the topic of the conference. An audio discussion of findings may also be published using the medium of podcasting – an emergent platform that (much like tattooing) engages a vast audience demographic, both socially and geographically. An online blog that has been started prior to the research will be carried out parallel to the research, and publications in both academic and tattoo-specialist outlets (such as ‘Total Tattoo’ or ‘Skin Deep’ magazine) will be sought. In addition to a thesis, a non-academic book that documents the research process will be created, with a non-specialist publisher being pursued.

This is in acknowledgement of the popularity of the research topic in contemporary Western culture, but also an effort to create a format that places tattooing within the more appropriate category of art and design publications, as opposed to specialist interest. Utilising such methods and disseminating the findings in such a way contributes to the presentation of notion as tattoo’s as a medium, providing a strong basis for the enrichment to both understanding and practice that the research aims to deliver.

While PhD theses exist that utilise practice within the methodology in creative disciplines such as glass (Song, 2014), illustration (Hoogslag, 2015), or calligraphy (Ling, 2008), contemporary Western tattooing is yet to be examined by such means. The research will implement practice as a method in a way that is comparable to existing practice-based methodologies such as those listed.

Lane, D. C. (2014) ‘Tat’s All Folks: An Analysis of Tattoo Literature: Tat’s All Folks’, Sociology Compass, 8(4), pp. 398–410. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12142.

Ling, M. (2008) Calligraphy across boundaries. Ph.D. University of Sunderland. Available at: http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/2929/ (Accessed: 3 January 2018).

Mace, M.-A. and Ward, T. (2002) ‘Modeling the Creative Process: A Grounded Theory Analysis of Creativity in the Domain of Art Making’, Creativity Research Journal, 14(2), pp. 179–192. doi: 10.1207/S15326934CRJ1402_5.

Méndez, M. (2013) ‘Autoethnography as a research method: Advantages, limitations and criticisms’, Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 15(2), pp. 279–287.

Song, M. J. (2014) Mechanisms of in-betweenness : through visual experiences of glass. Ph.D. Royal College of Art. Available at: http://researchonline.rca.ac.uk/1657/ (Accessed: 3 January 2018).

Tani, A. (2013) Multi-dimensional line-drawing with glass through a development of lampworking. Ph.D. University of Sunderland. Available at: http://sure.sunder- land.ac.uk/5030/ (Accessed: 3 January 2018).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed