|

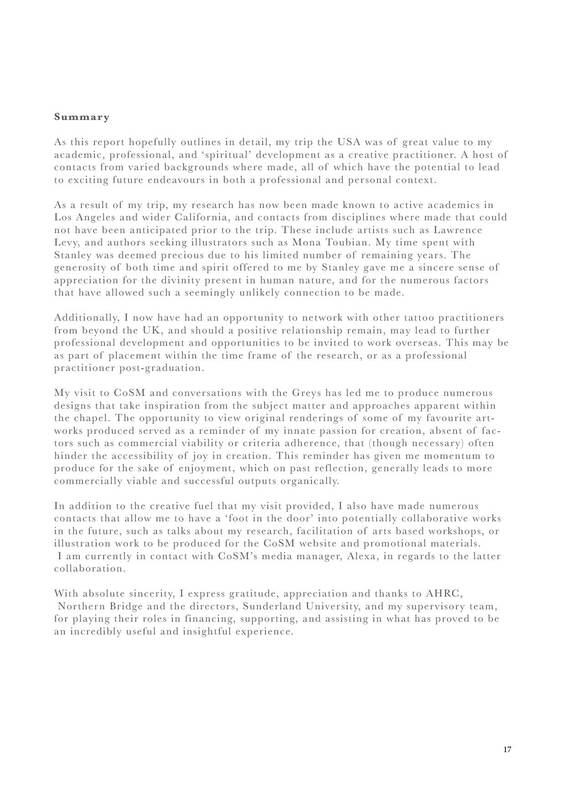

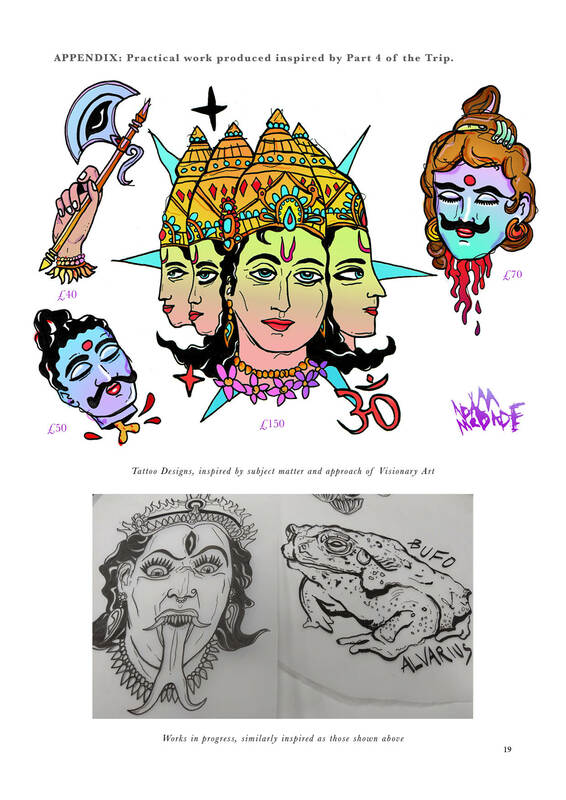

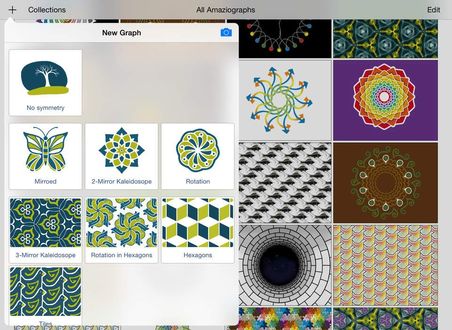

Overview This post reflects and records on my experience of creating and tattooing a mandala tattoo, utilising the application ‘Amaziograph’ and software ‘Adobe Photoshop’. This piece of writing aims in part to document one aspect of how technological advancements have affected tattooing practice, and to elucidate on the process of cultural production of tattooing - drawing parallels between theory and methods from more conventional creative mediums. In addition, the purpose of this writing is to contextualise the notion of the multifaceted role of the tattooist, from the perspective of the practitioner/researcher. Distinct from other creative disciplines, skill refinement and development of tattooing practice typically requires the skin of someone external to the practitioner. Development of skills and ability is only possible through repetitive practice, however due to the inherently collaborative nature of tattooing, sourcing ‘materials’ for practice (other people) can be challenging. In order to reduce this problem, I was advised to produce pre-drawn tattoo designs that may be offered on the Triplesix Studios social media pages, of the popular tattoo subject matter – the mandala. The rationale of this method is two-fold; despite Triplesix Studios custom operational system, multiple potential clients inquire within the store and ask to see ‘what designs we have’. It can be inferred that such clients are uncertain on what it is they hope to have tattooed, however still hope to obtain a tattoo. As a custom studio, books of pre-drawn designs (flash) are not kept or presented. The presentation of a pre-drawn image thus helps to encourage the indecisive client in design selection, following the typical format of advertising. In addition to assisting in design selection, the mandala design may be created in a time-efficient way. In contrast to the traditional Tibetan sand mandala, which is produced by a collective of Buddhist monks over a period of days in a ceremonial context before being wiped away to symbolise the impermanence of all things (anicca) and renunciation of attachments (Toupence, 2007, p.12), many tattooists conventionally now utilise an iPad and software known as ‘Amaziograph’ to produce mandala designs with relative ease and speed. Having such pre-set designs that are also commonly requested aids in increasing the potential of obtaining clients to tattoo, and practice tattooing as a result. Amaziograph is a drawing symmetry application that is designed to “support lessons for symmetry and tessellation and help students to discover the beautiful connection between mathematics and art” (Amaziograph Official Manual, 2018, p.2). Within Triplesix Studios and many other studios operating in a similar way, the software is used to create mandala designs. Utilising the mirrored kaleidoscope option of the software, pressure can be applied to the iPad screen (generally with the apple pencil) in which a grid format is presented, and a mark is made. The number of points on the grid may be chosen, and each mark is duplicated in perfect symmetry in accordance to the users’ preferences of repetition. This allows for the creation of an image that is directly transferrable as a stencil for tattooing. As a novice to producing creative works an iPad, I assumed the process would be difficult to grasp, however found it to be relatively intuitive. I was loaned an iPad from the studio founder, and produced a number of mandala designs that where set at the predetermined price of £50. A number of the designs where composed onto an a4 sheet and placed onto the studio countertop/shared on the studio social media. In addition to designs being exclusively in black, I also utilised Adobe Photoshop to inform colour selection. This was performed by opening the saved jpg mandala files in Photoshop and selecting a portion of the design using the magic wand tool, before filling the selection with a variety of tonal gradients on a separate layer. For each layer of the mandala (which may be understood as each section that is linked in that it is the same mark repeated), a new Photoshop layer was created and the gradient of colours changed. Experimenting with colours on separate layers allowed for multiple versions of colour ways to be explored with ease, the layers could be duplicated and altered accordingly. This method of practice is not necessarily traditional, in that mandalas are often tattooed in black ink exclusively, and the technique employed is that which is more in keeping with my personal approach is design work in more conventional disciplines (illustration, graphics, etc.). As I had expressed some scepticism in my ability to create mandala tattoos (due to having no experience in tattooing them), a desk staff member/colleague, Lesley, expressed an interest in having me utilise a space on her arm for my skill development. Lesley requested a colour pallet of brown, pink, and teal. This was attempted digitally (using the technique described above), however the outcome wasn’t deemed successful. In this instance, Lesley and I sat with a laptop and Photoshop software, exploring a variety of colour options, before committing to a pallet of teals, purples, and greens. The design was then printed and placed alongside the non-coloured image as a reference point for the colouring process. The placement of the design on the arm required 2 attempts. When applying stencils, the part of the body to be tattooed must be relaxed in such a way that is natural. This is in order to ensure that the way in which the tattoo will be viewed Is in accordance to a natural posture, rather than a posture of tension. The first stencil application appeared correct when the wrist was presented as an epidermal surface to which marks can be made upon (that is, when held outwards in a way that fully exposed the area of the body to be tattooed), however the stencil appeared off centre when viewed in a natural posture. The stencil was then reapplied in accordance to how it would be viewed when the arm was down by the side of the body, thus how the tattoo would be viewed in context. This consideration may be comparative to that of an illustrator designing a book cover, with the knowledge of titles, typography, and dimensions of the book in mind – while the illustration may appear successful when viewed out of context, when placed in context the same image may not work as affectively. The application of the tattoo outline followed the conventional format, of creating the outline of the tattoo initially using black ink and following the purple coloured carbon stencil to increase the likelihood of an accurate translation from source image to tattoo. Once the outline and black ink of the design was tattooed, the colour application procedure began. Unlike the outline process in which the aim was to accurately reflect the source image, the colour option sheet that was created was more of an informative aid than instructional brief. The colours on the print may not always be representative of the ink selections available to the practitioner or the level of saturation of pigment, and thus merely guide the process. The role I had taken in performing each aspect of the tattoo felt like it had shifted from outline to colour. When conducting the outline, the importance was placed on craft-like conduct – that is, “… a way of doing things” that is supplemental to attaining the desired outcome (Adamson, 2007, p.6). When applying the colour, the process felt more in keeping with design training in that it required the activation of a creative capacity that wasn’t relevant to the outline process. As a requirement to fulfil the desired tattoo outcome, my role as a practitioner for this particular brief required a different skill set to tattoos created that are in keeping with the craft-like conduct alone. The finished tattoo serves as a documentation of the interplay between technology and creative practice, methods sourced from design (photoshop as an informative aid to conduct) and craft approaches to tattooing practice. Bibliography

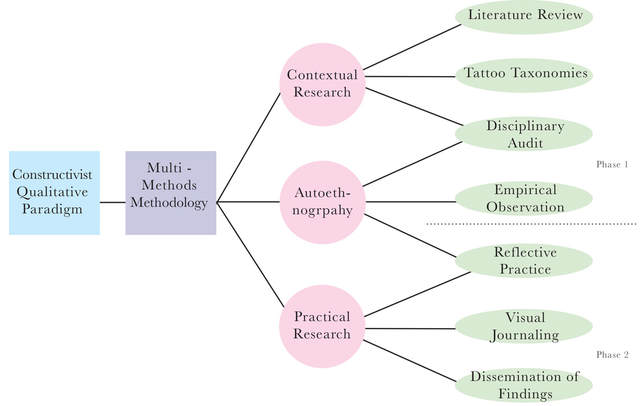

Adamson, G. (2007) Thinking Through Craft. 1st Edition. London ; New York: Berg Publishers. Amaziograph Official Manual (2018) ‘Amaziograph Official Manual’. Amaziograph. Available at: http://www.amaziograph.com/manual/AmaziographUserManual.pdf (Accessed: 14 November 2018). Toupence, J. (2007) ‘Tibetan Sand Mandala.’, Skipping Stones, 19(3), pp. 12–12. The format of the blog thus far has been mostly explanatory of the functional processes employed during my tattoo apprenticeship experience. The entries have been written in a heavily descriptive format of the steps taken in the conduct employed. This format of writing is potentially of value to the PhD research that is being undertaken, however requires a level of attention to detail that may not allow for the level of up-keep and post frequency that is desired. The explanation of the early stages of the apprenticeship are useful and informative, however are beyond the scope of inclusion to the PhD research due to the 40000-word limitation on practice-led study. Since the previous post in April 2018, many advancements in the apprenticeship process have been made. The most recent blog post was an account of activity of tattooing fruit skin that was actually conducted in September/October 2017, however since that time multiple tattoos on actual skin have been carried out (72, at the time of writing in October 2018). In order to keep the blog functioning as an up-to-date account of the apprenticeship to professional tattooist transition, and of the evolution of the research as it unfolds, an alternative approach to writing must be approached. By keeping the posts created in the same time period in which what is being described and considered, a more organic and thus accurate sense of the research journey is made visible. The posts that are to follow are intended to function as a format of dissemination of developing themes of inquiry from my PhD research, that are reflections of my ongoing studio practice. The purpose of the research is to utilise my embeddedness as an apprentice tattooist with a design background to elucidate on and explore the process of cultural production of contemporary Western tattooing. The methodology of my research is shown in the below diagram – included in this post to give an indication of what the future narrative of the blog may look like. The following text is taken from the methodology section of my most recent annual monitoring report, serving as documentation of the way in which the research is currently being conducted and shaped. During the academic year of 2018/19, the primary focus of the research is to focus on tattooing practice, in order to both improve professional skill, and to understand the process of cultural production greater, thus allowing for the implementation of design skills in professional conduct. A contextual overview of contemporary Western tattooing is necessary in order to position the research within the field. This includes reviewing the existing literature to discover areas lacking in clarity of understanding that may be pursued. The literature review is continuing to be conducted throughout the research process. Context has also been provided through taxonomizing stylistic approaches to tattooing, categorizing the name of each style in relation to its antecedent style. This is in order to document cultural history and to provide context from a visual and design perspective to contemporary Western tattooing, that the literature review highlights to be absent. Understanding on the process of cultural production of tattooing is lacking (Lane, 2014). This includes what tools are utilised to create marks of varying visual properties of tattoos, such as ‘liners’ or ‘magnums’, in addition to the process of client consultation, through to design formation, stencil, and actual tattoo. A disciplinary audit of the functioning of tattooing is necessary in order to provide a basis for practical investigation. Methods commonly employed by tattooists for self-promotion (such as the sharing of work on social networking websites, tattoo convention attendance, and guest-artist appearances) would also be recorded in order to document cultural history. The contextual overview will also be informed by an autoethnographic approach due to my embeddedness within Triplesix Studios as a designer who is working as a tattooist. As stated by Méndez (2013, p.280), “autoethnography allows researchers to draw on their own experiences to understand a particular phenomenon or culture”. Observations or ‘fieldwork’ of the process of cultural production will be documented in order to discover where introducing methods known from design practice may be appropriate in tattooing practice and provide insights that have been demonstrated to be lacking in literature. Phase 1 of the research provides understanding of context – phase 2 aims to expand on the findings to investigate tattooing as creative medium, using reflective practice and autoethnography. Reflective practice can be understood in accordance to the ideas of Schön; that the practitioner “...may reflect on the tacit norms and appreciations that underlie a judgment, or on the strategies and theories implicit in a pattern of behavior” (1984, p.3). Tattoos created would be evaluated through the documentation of its concept through to finished article in the form of writings, photographs, and presentation of methods used to create the design (visual journaling). A dated document of each tattoo created is also being maintained for reflective purposes. This process of visual journaling addresses the gap in knowledge, while also providing a basis for tattooing as both practice, and praxis (utilising knowledge gained from phase 1). After gaining authentic understanding of industry processes and confidence in tattooing, alternative models of practice would then be investigated in keeping with methods known as a designer. This would correspond with the processes identified for creativity by Mace and Ward (2002, p.184) who state that in order to enrich, expand, and develop a project an artist “engages in a process of idea development and extension through exploring the intricacies of that concept, building up a richness of form and content” (2002, p. 184). Implementing methods from design practice in tattooing is a means of investigating how contemporary Western tattooing may be enriched. In order to disseminate findings, multiple conference attendances will be made as the research unfolds, presenting emergent themes appropriate to the topic of the conference. An audio discussion of findings may also be published using the medium of podcasting – an emergent platform that (much like tattooing) engages a vast audience demographic, both socially and geographically. An online blog that has been started prior to the research will be carried out parallel to the research, and publications in both academic and tattoo-specialist outlets (such as ‘Total Tattoo’ or ‘Skin Deep’ magazine) will be sought. In addition to a thesis, a non-academic book that documents the research process will be created, with a non-specialist publisher being pursued. This is in acknowledgement of the popularity of the research topic in contemporary Western culture, but also an effort to create a format that places tattooing within the more appropriate category of art and design publications, as opposed to specialist interest. Utilising such methods and disseminating the findings in such a way contributes to the presentation of notion as tattoo’s as a medium, providing a strong basis for the enrichment to both understanding and practice that the research aims to deliver. While PhD theses exist that utilise practice within the methodology in creative disciplines such as glass (Song, 2014), illustration (Hoogslag, 2015), or calligraphy (Ling, 2008), contemporary Western tattooing is yet to be examined by such means. The research will implement practice as a method in a way that is comparable to existing practice-based methodologies such as those listed. Hoogslag, J. (2015) On the persistence of a modest medium : the role of editorial illustration in print and online media. Ph.D. Royal College of Art. Available at: http:// researchonline.rca.ac.uk/1696/ (Accessed: 3 January 2018).

Lane, D. C. (2014) ‘Tat’s All Folks: An Analysis of Tattoo Literature: Tat’s All Folks’, Sociology Compass, 8(4), pp. 398–410. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12142. Ling, M. (2008) Calligraphy across boundaries. Ph.D. University of Sunderland. Available at: http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/2929/ (Accessed: 3 January 2018). Mace, M.-A. and Ward, T. (2002) ‘Modeling the Creative Process: A Grounded Theory Analysis of Creativity in the Domain of Art Making’, Creativity Research Journal, 14(2), pp. 179–192. doi: 10.1207/S15326934CRJ1402_5. Méndez, M. (2013) ‘Autoethnography as a research method: Advantages, limitations and criticisms’, Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 15(2), pp. 279–287. Song, M. J. (2014) Mechanisms of in-betweenness : through visual experiences of glass. Ph.D. Royal College of Art. Available at: http://researchonline.rca.ac.uk/1657/ (Accessed: 3 January 2018). Tani, A. (2013) Multi-dimensional line-drawing with glass through a development of lampworking. Ph.D. University of Sunderland. Available at: http://sure.sunder- land.ac.uk/5030/ (Accessed: 3 January 2018). |

Beyond the Epidermis: Research Blog

A document of my experience working as a tattooist at Triplesix Studios, while also serving as a platform for my AHRC NPIF funded research as a PhD student in Design at the University of Sunderland. Archives

May 2020

Categories

All

|

-

Commercial Work

- The Northern Correspondent

- Love Serve Remember Foundation

- Praeger Publishers

- Misfit Press

- Restaurant Illustration

- Nesta

- Walwick Hall Boutique Country Hotel

- Cirkus IV—The Blue Star

- Scroobius Pip

- END. Clothing

- Worry Party

- Acoustic

- The Psychedelic Society

- Dr. Chris Ryan

- Dead Pirate Crew

- Firewords Quarterly

- Personal Work

- Tattooing

- Bio/Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed