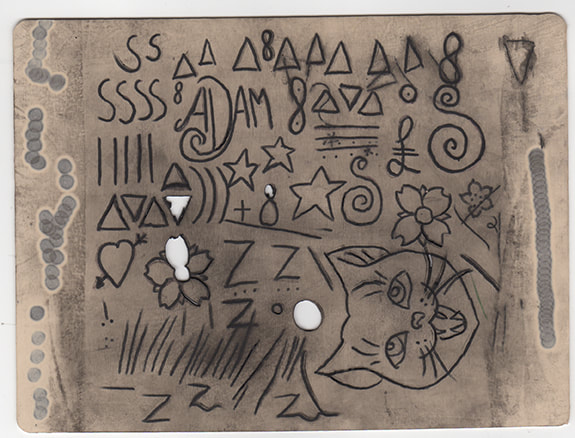

The symbols and marks drawn onto the fake skin where not chosen for aesthetic purposes, but for difficulty. Shapes such as the form of an ‘s’ and triangles/circles are thought to be difficult to tattoo perfectly. The purpose of inclusion of them on the fake skin was to learn how to approach such shapes and consider how the hand position may change, the positioning of the body while tattooing to adhere to a shape may adjust, and how to perform what looks like a continuous line of consistent depth without actually being executed in a single pass.

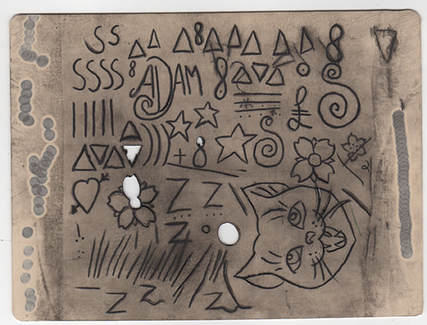

As evident in the image, the pressure applied was too much in particular areas and has caused tears in the surface, however this is also due to the poor quality of the materials and not representative of actual skin. The image below shows the finished result of the exercise, with the fake skin being taken away from the ‘pound of flesh’ to reveal areas that had been accidentally made.

Adam McDade

Illustrator, Tattoo Apprentice, and PhD Research Student

RSS Feed

RSS Feed