M-Shed, Bristol. 22/7.

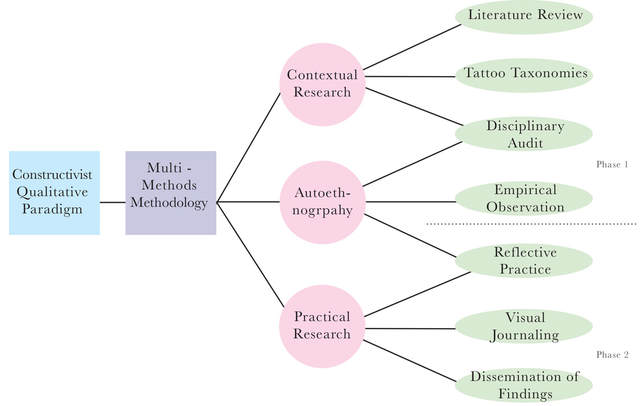

Prior to the conference commencing, multiple workshops where held on varying themes that involved autoethnography. My research adopts a multi-method methodological approach combining autoethnography and practice, and so from the available selection, ‘doing arts-based research’ was deemed the most relevant. The personal aim of attendance was to gain some first-hand insights into how practice and autoethnography may relate, from those who utilise it as their established methodological approach.

Kitrina Douglas lead the session, and introduced aspects of her autoethnography work that utilised creative practice (such as music, poetry, and film-making) while working with marginalised groups dealing with taboo topics. Douglas shared a piece of performative autoethnography in the form of a song that she had written when working with marginalised ladies in Cornwall on a 4 day retreat. The song contained lyrics that told the story of one of the ladies’ repression, but also that where her own personal narrative that reflected the sentiments of the lady who she was working with. Douglass explained how the knowledge that was gained was not merely retold in the form of words in such a way that may be deemed exploitative of their biographical narratives, but shared in vulnerability by relating to the narrative personally. As a result, the research output in the form of song was deemed more accessible to non-academic audiences, and able to communicate in such a way that was beyond words alone.

The workshop also involved a 2-stage task. Kitrina began the task by whispering a word into the ear of a participant, who was then asked to go into the centre of the room and communicate the word using an absence of the spoken word and through the body and gesture alone. This was then guessed by other participants. The process was followed so that each member of the group was able to perform their given word. On completion, Kitrina asked each of us to write down responses to 3 questions;

1/ How did you feel when given your word?

2/ How did you feel after performing your word?

3/ How did you feel when watching others perform their word.

Kitrina then read out our responses in such a way that was anonymous, highlighting the commonalties in our experiences, but uniqueness in our words. Kitrina also utilised the task to serve as an example of how we communicate through much more than words alone, highlighting the use of arts-based outputs when dealing with autoethnographic material.

I feel that as a result of attending the workshop, my understanding of what autoethnography is, how it can be utilised and expressed, and the validity of its employment as a research methodology has been enriched. While my PhD research takes the form of a more traditional autoethnographic approach, my understanding of its versatility of application and multitude of form has given me confidence in claiming that I am utilising a form of autoethnography which I now understand cannot be pinned down to a singular approach.

Attendance of presentations of other researchers / practitioners utilising autoethnographic methodological approaches, and presentation of research. 22 & 23/7.

Both the Monday and Tuesday of the conference featured presentations from autoethnographers from a variety of disciplines. The session on Monday the 22nd featured more established autoethnographers such as Ken Gale and David Carless. The work they presented took the form of traditional paper readings, conventionally formatted conference presentations, as well as musical and narrative performances. When the content was presented, the utilisation of the body in its various forms of expression assisted in the communication of the ideas, echoing the sentiments of the workshop held earlier in the day by Kitrina Douglas.

An example of this included the presentation titled ‘Trickster Tales’ by Lapin Ammattikorkeakoulu, who presented her autoethnography based on a tradition of call and response that is native to her African origins, and required the audience to recount a story (including actions) to the person who was situated next to them. Lapin then spoke on oral history and storytelling, using her personal narrative and embodied expression to communicate her messages. Other presentations included the themes of parenting in its various forms, and consisted of narrativised anecdotes that speak of the challenges when dealing with topics of toilet training, technology, and discussions on difficult topics such as religion when talking to children. The anecdotes where unique to the researchers, but generalisable in so much as the experiences have common equivalents that can be drawn.

I was given the opportunity to present my own research on Tuesday the 23rd, to a receptive audience of around 30 people. As I presented, I became aware that my presentation style was more fluent than it has been in the past due to social anxiety. Despite this still being something difficult to contend with, I recognised that my knowledge of the content that I was delivering allowed me to bypass my emotional responses to public speaking and communicate effectively. As I was speaking, I was made aware of audience engagement with the content through eye-gaze and laughter (where humour was intended). When reading an excerpt of my autoethnographic writing, I also heard an audience member state, ‘Yes! That’s it!’, which assisted in alleviating insecurities surrounding uncertainty as to if I was performing autoethnography ‘properly’. Due to time constraints that where the result of technological issues, no question session was able to be held, however multiple meaningful and mutually encouraging conversations with other presenters ensued throughout the day.

As the day continued, I attentively watched other presenters share their work on themes such as working as a counsellor dealing with themes of political contrast between therapist and patient (Travis Heath), working with colleagues with challenging attitudes while caring for patients with dementia (Gary Hodge), and dealing with the harmful institutional pressures and expectations when working within academia (Karen Lumsden). While watching the presentations, I recorded observations and notes on realisations that I was gaining on what autoethnography really is, and how it is valuable when dealing with topics that are difficult to communicate and document in more traditional methodological approaches.

The notes included comments such as;

‘Autoethnography acknowledges that research is conducted by a human, and doesn’t separate research from the researcher’

‘Autoethnography brings the somatic experience to the subject that is being researched, representing a topic with authenticity and recognition of nuance’.

‘Autoethnography is what Jack Kerouac does’

‘Autoethnography is a methodological approach that recognises the notion that we are spiritual beings having a human experience’

Though these notes where for my own understanding, they have been included in this report in the spirit of autoethnographic inquiry, as they are records of ideas / thoughts / questions that have been triggered by participating in the conference. In a similar fashion, diagrammatic forms where sketched based on personal interpretation of other presenters’ ways of utilising autoethnography, and how it is appropriate and valid to my own research. These included a visual response Fiona Murrays account of a spin class, that interweaved theory with both chronological narrative and internal workings, in recognition of the experience of participation in such an event. The notes made where not related to the presentation content alone, but what can be learned indirectly from having been present for the presentation.

Summary

Attendance at the sixth British conference of autoethnography allowed me to have opportunity to engage with other practitioners using autoethnography to uncover information that is under represented. In addition, I was able to present my research to a knowledgeable audience and gain feedback, learn of the research of others that may be drawn upon to enhance my own understanding, and introduce my research to a network of (hopefully) potential future colleagues. As a result of my attendance, I feel that I am more confident in both presenting research and in my use of autoethnography, and engaged with my methodological approach as much as I am the subject of my research. I am very grateful to Northumbria-Sunderland CDT directors and AHRC for allowing me the opportunity to have participated in what I deem the most valuable conference I have attended to date.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed